How Digital Stories from the Farm Spark Market Innovation

- Ceyda Sinag

- Sep 3

- 7 min read

Written By Ceyda Sinağ, Post-Doc at Sabancı University, Turkiye

If I ask you to picture an influencer and their everyday lives, most of us will likely come up with similar answers. Unless you have read the IJRM article in press, "From Social Feeds to Market Fields: How Influencer Stories Drive Market Innovation" by Professors Julien Cayla (Nanyang Business School), Kushagra Bhatnagar (Aalto University School of Business), Rajesh Nanarpuzha (IIM Udaipur), and Associate Researcher Sayantan Dey (IIM Udaipur). Their research not only disrupts the stereotypical image of an influencer but also challenges the premise that social media influencers primarily serve as brand intermediaries.

Influencers driving market innovation

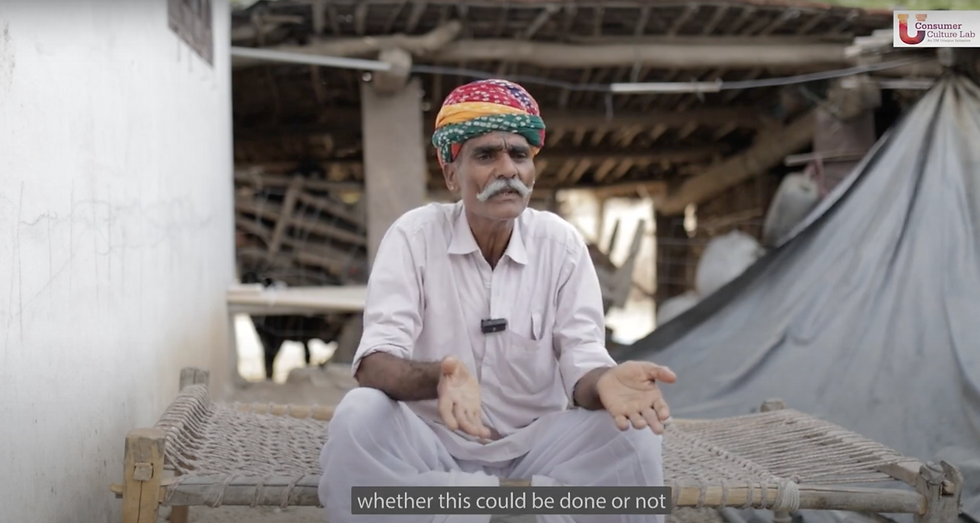

The role of influencers as brand intermediaries is a key focus in marketing literature. However, in this paper, the authors show that there is more to influencers than being another advertising channel. They chose a context – agriculture and farming - which was less familiar to marketing research. Through an ethnographic study of farmer-influencers in rural India, the authors highlight the power of influencers’ stories in driving market innovation.

Who are these market innovators? Let me first introduce the farmer influencers before turning to how their storytelling drives market innovation. It all starts with farmers in India who try out new farming techniques, crop choices, and sales methods, and share their experiences and insights with other farmers on social media. These farmer-influencers drive market innovation through their digital storytelling by three mechanisms: redefining market understanding, cultivating market agency, and redistributing market authority. For instance, organic farmer and influencer KP Sihag observed that government scientists provide detailed technical knowledge about plant nutrients, which lacks practical utility. In contrast, he creates grounded stories that help farmers identify and address nutrient deficiencies. Such stories make crucial knowledge more accessible and relatable. Farmer-influencers’ digital storytelling also changed the way farmers saw themselves – from being passive recipients of existing market conditions to active, curious, and risk-taking market participants. Finally, influencers’ narratives helped disrupt existing top-down power hierarchies in the overall farming marketplace, helping less powerful contextual experts gain more authoritative roles in the market.

These farmer-influencers are part of an emerging market characterised by institutional voids and infrastructural limitations. The authors reveal that in such settings, unlike in developed markets, a focus on storytelling rather than on giving out technical information can effectively address institutional voids.

How farmer influencers captured the authors’ attention

The authors came together through the Consumer Culture Lab, founded by Julien and co-chaired by Rajesh at the Indian Institute of Management (IIM), Udaipur. Julien realized that many people, including his students, imagined influencers as attractive men and women leading glamorous lives and promoting products gifted to them by marketers. But during a conversation, Julien's friend, who managed South Asia operations for a major agricultural fertilizer brand, mentioned that he had been working with Indian farmer-influencers and showed him some of their YouTube videos. Julien was fascinated by the contrast between these farmers and the usual glamorous image of influencers. His initial idea was to present this stereotype-shattering case to his students. However, it turned out to be an excellent research context to tell a powerful story about change and innovation in India and to change the stereotypical image of the influencer in marketing scholarship.

Not your typical marketing fieldwork

The pace of digital change in India has been revolutionary. Cheap Android smartphones, some of the cheapest data prices in the world, and high-speed Internet coverage even in remote areas helped millions of Indians cross the digital divide almost overnight. For Julien, the rural digital revolution was a fascinating research context. However, conducting ethnographic research in such rural, remote settings was a major challenge.

Six months after starting the project, the COVID-19 pandemic broke out. The authors adapted by interviewing farmers over the phone or via video chat. But it was not enough to become proper insiders into their informants’ lives. Also, as Kushagra mentions, the authors’ and farmers’ lived realities were so distinct that they struggled to find common ground when talking on the phone. Julien remembers spending all night searching Google to figure out the techniques farmers described. They needed "thick description," that is, a grounded, contextualised understanding of the field. So, after a two-year pandemic-enforced hiatus, all of them literally went to the field, which came with a new set of challenges. Sayantan shares that finding and meeting geographically dispersed influencer-farmers and their audience was not easy. Doing ethnographic fieldwork well demanded considerable investment of time.

“I was in the field in the middle of the summer. The challenges were real, ranging from scorching heat to muddy grounds. Yet, the influencers gave me long hours, days probably, so that I could discuss how they have shaped their own journey.”

- Sayantan

Despite the challenges, doing ethnographic fieldwork was quite rewarding. Sayantan remembers how striking it was to see a farmer carrying a DSLR camera and a tripod, rather than agricultural tools, when heading into a field to record the voices of fellow farmers. Kushagra and Julien speak of their excitement at the ethnography revealing and bringing to life a world usually hidden and remote from the pages of mainstream marketing scholarship.

It is the friendship that counts

For the authors, the fieldwork was challenging, but it also gave them the chance to share some extraordinary moments. The friendships forged in those field visits became the highlight of the seven-year project. For Julien, one such extraordinary moment was when a farmer influencer asked to feature the authors in one of his YouTube videos.

“To have a video on YouTube that features the four members of the team being interviewed by one of their informants - that's one of the things in anthropology. It's not only about the researcher trying to make their point about the informant, but also about giving the informant the power to tell their own story. And I thought that was a great example of that.”

- Julien

Other rewarding memories were the two-and-a-half-hour car rides to and from the villages, each ride full of fresh insights and exciting discussions, and the many debrief and brainstorming sessions across coffee shops in Udaipur to theorise from the field data. For Rajesh, a standout aspect was the hospitality – for instance, the freshly-cooked food villagers offered them. He talks about farmers’ efforts to make the team feel at home:

“When you go there, influencers make it a point to take you around the whole village, make sure that you are introduced to the key people in the village, and they make sure that you are a guest and that everyone should know you.”

- Rajesh

A non-academic windfall of doing this project together was that they started the project as co-authors and colleagues, but ended it as friends. As Julien puts it, "Life is too short in academia to work with people you don't enjoy working with." He continues, telling me that the best part of the project was no battle of egos. Kushagra supports this by explaining that they are keen to listen to each other. As a bonus, Kushagra shares with us advice he received from Julien on choosing co-authors: “Can you hang out with your co-author when you're not working with them?” If the answer is yes, then that is the right person to work with.

The guiding role of the review process

Having a compelling context is simply the first step in a research project. Often, the more tricky, difficult part is to find value beyond that immediate research context. Kushagra explains why and how the IJRM review process enabled them in this attempt.

“A lot of qualitative research runs the risk of becoming context fetish. The authors say, 'Look how extreme, and amazing my context is.' But then the question becomes: So, what? What do we actually learn from it? We could have fallen into that trap… The review process really helped us avoid that. It pushed us to constantly keep an eye on the bigger picture and to ask: what does this context reveal more broadly?"

- Kushagra

Julien adds that theorizing from context is common in CCT research, but it is not an easy task. This is because authors must craft multiple iterations to generate meaningful theory. With this paper, comments and suggestions from the IJRM reviewers and the associate editor helped authors to further refine their story from a storytelling and innovation angle.

Read the paper

Interested in reading “From Social Feeds to Market Fields: How Influencer Stories Drive Market Innovation” Read the full paper here.

Want to cite the paper?

Cayla, J., Bhatnagar, K., Nanarpuzha, R., & Dey, S. (2025). From social feeds to market fields: How influencer stories drive market innovation. International Journal of Research in Marketing.

Meet the Authors

Who is the researcher from any field you would like to sit down to lunch with? What would you say to him/her?

Julien Cayla

Associate Professor of Marketing at Nanyang Business School

These days, I work on the topic of emotional energy, which refers to the energy you get from interactions. Sociologist Randall Collins has a book about it, and I’ve never met him. I guess the question I would ask him is whether he’s used any of the insights he has about energizing experiences in his own life. How energized is his own life? Does he apply his research to his own life? I’m always interested to see if people use the insights they get from their research in their own lives.

Kushagra Bhatnagar

Assistant Professor at Aalto University School of Business

I would love to bring Karl Polanyi back to life, have lunch with him, and ask him what he makes of the current AI mania, which seems to have separated economy from society almost irreversibly.

Rajesh Nanarpuzha

Associate Professor of Marketing at the Indian Institute of Management Udaipur

I was reading about the idea of what it means to have a growth mindset, something widely used in education and psychology. I thought it would be quite interesting to meet Carol Dweck, who has worked extensively in that area. I would like to ask her how a growth mindset can be cultivated by academics.

Sayantan Dey

Research Associate at the Consumer Culture Lab, IIM Udaipur

Recently, I've started reading Michel Foucault a lot, and I wish I could meet him. Since I’m working on influencers, and podcasts are everywhere these days, maybe a podcast session with Michel Foucault would be nice.

This article was written by

Post-Doc at the Sabancı University, Turkiye

Comments